Last week, as a thank you to the Fort Frederica RV volunteers, Ranger Michael took us all on a trip to Cumberland Island National Seashore. Ranger Michael has been offering to take us over to Cumberland every year we have worked at Fort Frederica. This year I pushed him to set a date so we could actually do it. The idea, initially, was to do a volunteer project. But Ranger Michael decided, instead, to make it an educational trip. We saw so many things and learned so much that I will break up writing about the island into two posts: Cumberland Island (today) and the Carnegies on Cumberland Island (Wednesday).

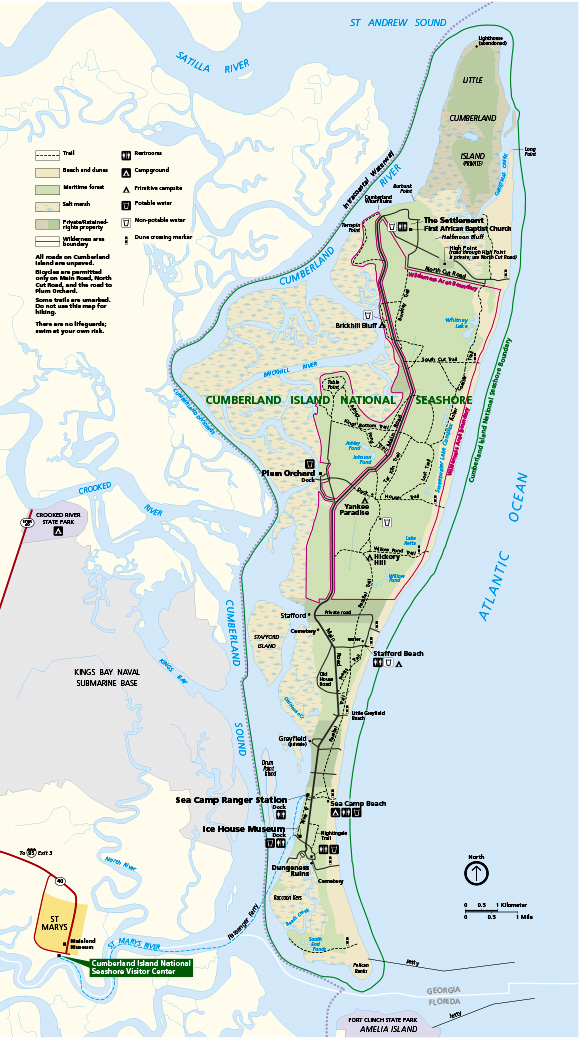

Cumberland Island National Seashore is 90% of the island, with the rest of the land held privately. The island is the westernmost of all the islands on the Atlantic coast of North America. It is the largest of the sea islands of Georgia. The southern end of the island is the developed part of the National Seashore and the northern end is wilderness.

We got on the National Park staff boat in St. Marys at 9 a.m. We had to leave Fort Frederica at 7:30 in order to get there on time. Michael arranged for the boat to leave an hour later than usual, which we all appreciated. Besides the eight volunteers, there were also two archaeologists from the Southeast Region who are doing 3D mapping of sites on the island. The curator for Cumberland also went with us. We left about the same time as the Cumberland Island public ferry, but were able to go faster and arrived before they did.

The boat ride to Cumberland Island is about 30 minutes. We were thankful there was a cabin on the boat because it was cold and windy. Although we woke up to rain, the rain stopped by the time we got to St. Marys. It did stay overcast the rest of the day. On our way to the island, Michael pointed out some of the things we could see. Amelia Island and Fort Clinch were to the south. Jekyll Island and St. Simons to the north. Kings Bay Naval Base is to the west.

We landed at the Ice House Museum Dock, which is the southernmost access point on the island. The public ferry docks at Ice House Museum Dock and also at Sea Camp Dock. The Ice House Museum is part of the historic Dungeness Ruins, which I will write about more on Wednesday. After taking a look at the museum, which contains a short history of the island, we boarded a van for our educational tour.

Visitors to the island ride the public ferry and can take a Land and Legacy Tour, run by a private concessionaire. The ferry ride is $34 per person and often sells out, especially in the spring and summer. The Land and Legacy Tour is $45 per person and lasts six hours. That tour hits many of the places that we went with Michael. If you don’t take the tour, you have until 4:45 on your own. You can walk the one-mile loop to Dungeness Ruins or spend the day on the beach. Anything else on the island is too remote to be accessible.

Campers can stay up to seven nights at Sea Camp, which is the only place there is potable water and cold showers. There are no stores on the island, so when campers come they must bring everything they need for their stay. There are several primitive campsites on the island which are accessible by a long hike or by boat. We don’t think of the islands off Georgia’s coast as being remote, but Cumberland Island definitely is.

Once we boarded the van, Michael gave us a great tour of the island. We saw the Dungeness Ruins and avoided piles of horse manure as we walked around. The archaeologists were mapping inside, so we had an opportunity to walk inside the ruins a bit. The park service has stabilized them, but the piles of rubble were impressive. About 150 wild horses live on the island, abandoned by the people who lived on the island in the 1800’s and early 1900’s. They roam all over. While it was fun to see them, they certainly left a mess on the lawns.

Our next stop was the Carriage House, now being used as a maintenance shop. We were pretty impressed at the size and scope of the shop. Maintenance rangers come out on the staff boat and work all day, going home at night. None of the rangers stay on the island overnight. As we drove through the island we got an idea of the scope of the maintenance required. The first few miles of the 14 mile road on the island are “improved” which means they are hard-packed sand. But most of the road is not improved and is very rough. None of the roads or trails on the island are paved. It takes close to an hour to drive from one end of the island to the other.

We drove by the Stafford House, which is a privately owned building that will become NPS property when the current owner dies. There are several properties like that on the island. The park service technically owns them and is responsible for maintenance to the homes. But the owners are allowed to do whatever they want with the land and building until they die. The Stafford House needs a new roof, which the current residents refuse to pay for. So, does the park service pay to replace the roof now, to the benefit of the people who will live in it for an indeterminate amount of time, or do they replace and repair the house when the current owner dies? Michael, as the Resource Manager for Cumberland Island, is in charge of those kinds of tough decisions.

Another smaller house recently passed into the park service’s care. Cumberland Island was awarded a grant to remodel the house and use it as a museum and new ranger contact station. The building will be a good resource for the park, but the cost of remodeling on Cumberland Island is exorbitant. Replacing the roof on Plum Orchard Mansion recently cost the park service 1.2 million dollars.

The island is dotted with smaller cabins and outbuildings that the park service is using to house volunteers who are doing various projects on the island. We drove by several of them, with Michael saying he would be glad for any of us to volunteer anytime on Cumberland. Living on an isolated island might sound sweet – if you are prepared.

The biggest problem is the ferry which only runs once a day during the winter and spring. It leaves the island at 4:45, but doesn’t leave St. Marys until 9 the next morning. You can ride the ferry to St. Marys, drive to the grocery store, do whatever else you need to do on the mainland, but then you can’t get back to the island until the next morning. Where do you stay overnight? What do you do with the groceries? Most of the volunteers are only on the island for a week or two at a time, so they take what they need when they make the trip to the island. A few of the volunteers who stay longer have their own boats.

Michael gave us a behind-the-scenes tour of Plum Orchard Mansion (more Carnegie stuff on Wednesday). We made a quick stop at Brickhill Bluff, which is an impressive 40 foot sand cliff on the marsh side of the island. The bluff has maritime forest anchoring it on the top, so it is relatively stable despite the tidal basin beside it. It was one of the few things called a “bluff” in costal Georgia that is worthy of the name.

We took a lunch break at The Settlement which used to be an independent African American community on the north end of the island. Most of the people in the settlement worked for the hotels on the island or in the mansions of the wealthy families. Some were fishers or loggers. The only house still in decent shape at The Settlement belonged to Beulah Alberty. After her death the park service converted the house into a small African American museum and restrooms. The building has the only restrooms available on the north end of the island although there is no potable water.

The most famous building in The Settlement is the First African Baptist Church built in 1937. There are no services at the church but you can get married in the church with park service permission. On September 21, 1996, John F. Kennedy Jr. married Carolyn Bessette at the church.

Anyone can get married in the church, but the National Park Service does not provide transportation. Unless you and your soon-to-be spouse and guests plan to ride bikes fifteen miles to the church, all arrangements must be made through the Greyfield Inn, which also happens to be the only place to sleep on the island other than the campgrounds. Rooms average $750 per night which includes meals. The inn is owned by descendants of the Carnegies. Unlike most of the other private land that has been pledged to the park when the owners die, the owners of Grayfield Inn have no plans to sell, so it may end up being one of the very few private land holdings left on the island.

After our time at The Settlement we headed south again. We stopped at the remains of the slave cabins at Stafford House. There are 24 chimneys remaining of the original cabins. Robert Stafford had an unusually lenient attitude toward his enslaved people. When the slaves had finished their tasks for the week, they could earn money their own money working for other people. After emancipation these independent people were well positioned to buy their own land and own homes. The National Park Service is stabilizing the chimneys.

Our last stop was a trip to the beach. We went to the Sea Camp beach, so we could see the primitive campsites at Sea Camp. They are getting ready to build new bathhouses and the park service is debating how to have restrooms and potable water while the new bathhouses are being built. The beach is about a mile across the island from where the ferry docks at Sea Camp. Consequently all the campers have to haul their gear the mile from the dock to their campsite. But once they get to the campsite, they have the beach all to themselves, especially after the ferry leaves.

Cumberland Island has 17 miles of pristine, undeveloped beach. It is beautiful and wild, probably the most isolated beach on the eastern seacoast. We would have loved to spend more time exploring but it was about 46 degrees and windy, so not the best day to lounge or walk on the beach.

Our day at Cumberland Island came to an end by taking a group picture back at Ice House Dock and boarding the staff boat for the ride back to St. Marys. We all had a very enjoyable and educational visit to Cumberland Island. Most of us had thought about volunteering there at some time – Michael can be very persuasive – but agreed that the logistics were more than we wanted to tackle. But we were glad to see the island and learn about it. We were also very grateful to Michael for saving us the almost $100 each it would have cost to ride the public ferry and take a tour.

Cumberland Island National Seashore is a beautiful and isolated place. Definitely worth a visit or an overnight stay when you want to get away from civilization. Our visit made us appreciate the challenges facing the park service in the transition from private to public land management.