The day after hiking in El Malpais National Monument, Tom and I visited El Morro National Monument. The two monuments are only a few miles apart, but they are extremely different. Those of us who only speak English would say that the two names look alike but that is just because the start with “el” which is just “the” in Spanish and an “m.” El Malpais is all about volcanoes and lava. El Morro is about humans leaving their mark on the land.

The day after hiking in El Malpais National Monument, Tom and I visited El Morro National Monument. The two monuments are only a few miles apart, but they are extremely different. Those of us who only speak English would say that the two names look alike but that is just because the start with “el” which is just “the” in Spanish and an “m.” El Malpais is all about volcanoes and lava. El Morro is about humans leaving their mark on the land.

El Morro National Monument is on NM 53, 42 miles from Exit 83 on I-40. In order to get there, you drive along the edge of El Malpais National Monument and can see El Calderon and the ice caves on your way. But El Morro is not in the lava fields. Instead, it is a cuesta: a long rock formation gently sloping upward, the dropping off abruptly at one end. Long, vertical joints crease the face of the cliff at the one end.

On this smooth stone, people who journeyed past El Morro inscribed names, dates, and sometimes poems. Today the monument preserves these names. There are Native American petroglyphs and signatures and stories from the 400 years of Euro-Americans passing by. The Zuni call it “place of writings on the rock.” The Spanish called it El Morro – the Headland. Anglo-Americans called it “Inscription Rock.” People stopped here because it was a landmark but also because there is a deep, shaded pool of sweet water from the runoff of the cuesta.

The petroglyphs on the rock are from the Ancestral Puebloans, who also built a small gathering of homes on top of the cuesta. There is a three-mile trail up to the top of the escarpment, but it was very cold and windy the day Tom and I went so we did not climb up. Instead, we walked the half-mile trail by the inscriptions. You can borrow a guide book from the Visitors Center that helps you read the 2,000 plus inscriptions.

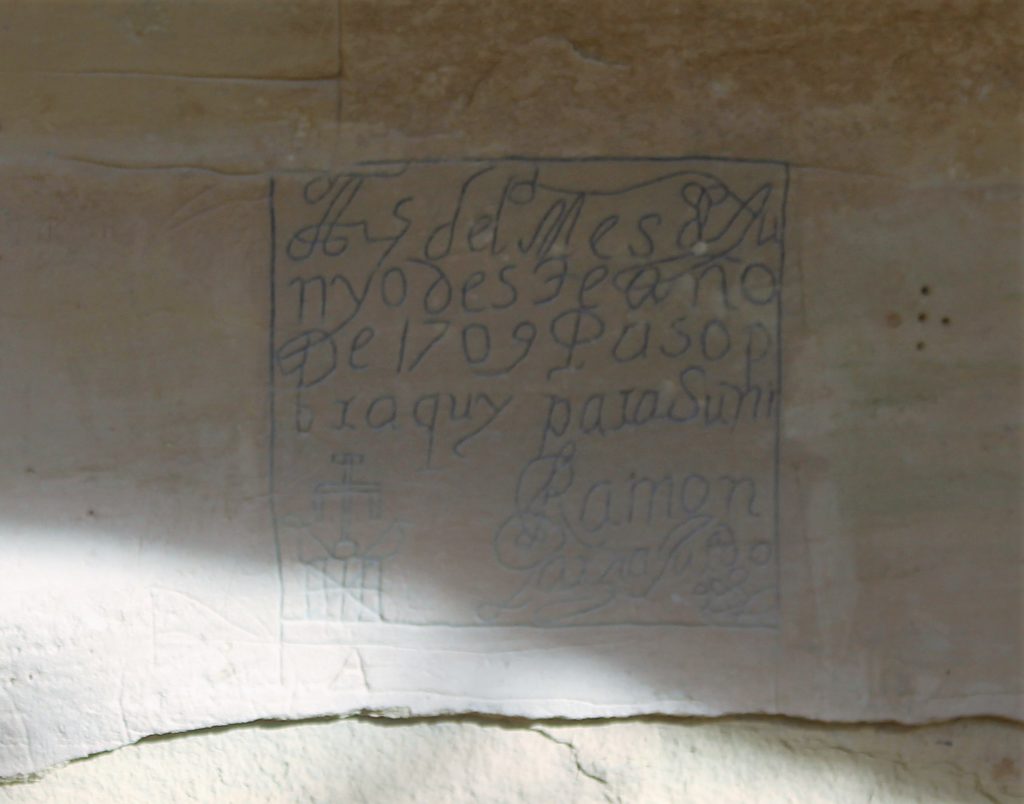

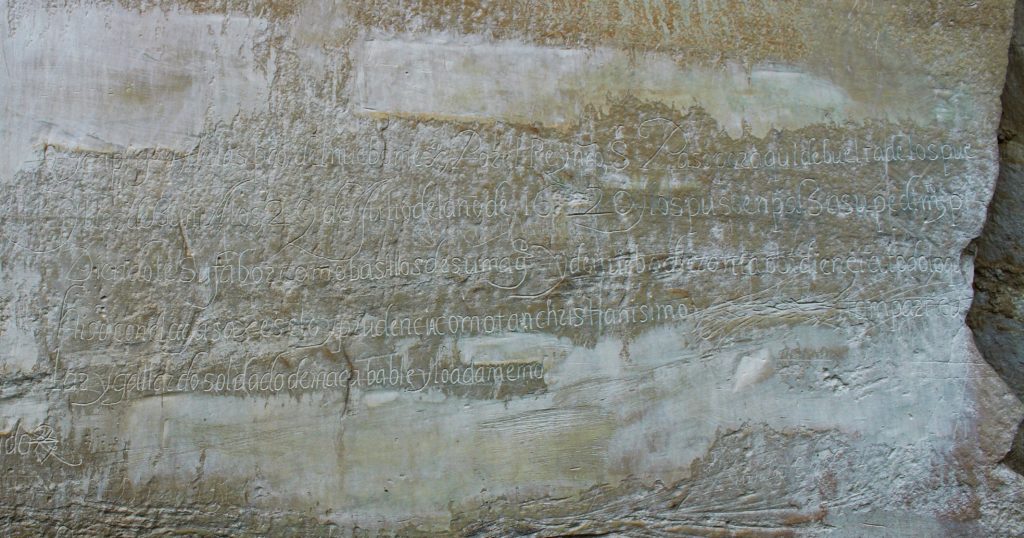

The first Euro-Americans to inscribe their names on the rock were the Spanish. The oldest Spanish inscription was made by Don Juan de Onate in 1605. Onate led the first group of Spanish colonists to New Mexico. Governors, soldiers, and priests who passed by also left their marks. The guidebook translated the faint, Spanish writings for us so we could see them. “Governor Don Juan de Onate passed through here, from the discovery of the Sea of the South on the 16th of April, 1605.” Another Spanish inscription read, “General Don Diego de Vargas, who conquered for our Holy Faith and for the Royal Crown, all of New Mexico, at his own expense, was here in the year of 1692.”

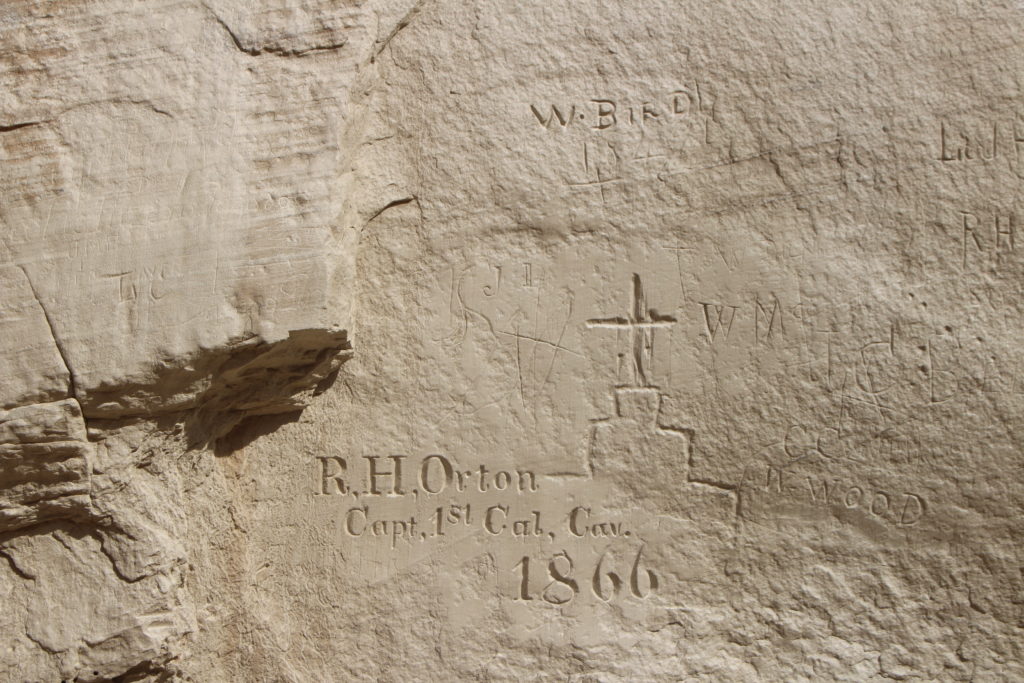

After New Mexico became an American territory in 1848, soldiers and explorers from the United States started leaving their mark on the rock. Lt. James Simpson and artist Richard Kern made a record of all the inscriptions in 1849, leaving their own signatures behind. P. Breckinridge made his mark when he passed by as part of the Army’s camel brigade. Pioneers passing by in wagon trains left their marks. A Union Pacific survey party stopped by in 1868 and all the people in the group signed the rock.

El Morro became a national monument in 1906 and further carving on the rock was prohibited. Because the rock was no longer on the route through the area, the signatures and other inscriptions are fairly well preserved. Over time, however, the sandstone erodes and suffers water damage. National Park Service rangers have tried various techniques to preserve the inscriptions. Bolts and cables hold some of the towering rocks in place.

Tom and I were fascinated by El Morro National Monument. We thought it was one of the most interesting places we have been. There are so many opportunities for interpretation: Ancestral Puebloan, Zuni, Spanish, and American. All of human history in the United States represented on the face of one cuesta.