Fyrkat Viking Fortress was our destination on our first visit to Denmark. The ship docked at Aarhus (two a’s if you don’t have a Danish keypad, Å if you have the Danish keypad). Aarhus looked like an interesting city with some good stuff to see, but we were ready for some Viking history. We boarded a Viking bus with our guide Jakob and driver Hans and headed out.

Fyrkat Viking Fortress is located in the town of Hobro, Denmark. It is a recreated ring fortress built by Harald Bluetooth in 980. Inside earthen walls, there were sixteen buildings arranged in four groups that corresponded to the four points of a compass. There are five ring fortresses in Denmark, all built in the same style and at the same time. The Fyrkat Viking Fortress was destroyed by a fire around 1000, so it had a short lifespan.

Over time the ring was leveled, but archaeologists excavated the site and the earthen wall was reconstructed. Concrete markers show where the posts for the buildings were set. One of the longhouses has been reconstructed outside the ring. Jakob, who is an archaeologist, told us that the longhouse was their best guess of what it looked like. They have good support for their guess, but there were no pictures or blueprints.

It was interesting to see the longhouse and then walk around the ring. It was also windy and cold, especially on top of the ring. The grass is mowed by Gutefaar sheep, an ancient breed that sheds its coat instead of needing to be sheared. There was wool lying around the circle and sheepy surprises all over the place.

After our visit to the Fyrkat Viking Fortress, we got back on the bus for a short ride to the Living Farm or Vikingegaarden. This was the surprise hit of our tour, at least for Tom and me. Our tour description said the farm has nine recreated buildings from a nobleman’s farm around 1000. But when we got there, we found each of the nine buildings staffed by living history people, living as if it was 1000. These were our kind of people, and they all spoke great English.

There was a group of men making iron for the blacksmith. When Tom is a blacksmith, he gets his iron already made and shaped into rods. These guys were digging rocks out of the peat bogs, heating the rocks up in a charcoal furnace, and melting the iron out of the rocks. Then it could be passed on to the blacksmith who could heat and beat it into tools. I knew Tom would be talking to these men for a while, so I ventured on.

I found a couple that was making their lunch in a longhouse using a modified bake oven. The oven had a hole in the top and the smoke went out another hole in the roof. The wife was making a pan bread using an iron skillet and she had cheese curdling near the fire. There was a loom with a weighted warp in the corner. All of the living history people were wearing linen or wool. I asked if they made their own cloth for their clothes and they said no, it would be too time-consuming. Don’t I know it!

There were two mama sheep and three lambs outside the buildings. One mama had been tied up to a log a little way from her lambs. She seemed pretty content until two little boys started playing too boisterously with her lambs. Then she bleeted and baaed and pulled on the log until she got over to where her lambs were. She was a very determined mama.

Instead of just watching, I spent most of my time talking to the different living history people. One woman explained how they got the wool from the Gutefaar sheep. If the sheep was tame enough, they could pluck it during the spring. If not, you had to pick up the wool from the ground and the off the trees and off the fences. It was easier to pluck it, but the sheep are not very tame, despite living in the compound.

Another woman was tanning hides. After the hide was scraped, they boiled it with willow bark and “brain soup” until it got soft. Although they liked to wear linen or wool next to their skin, the skins were warm and waterproof, good for capes, blankets, and shoes.

An armorer was explaining weapons and shields. There was a space for children to play games. A modern playground had a Viking theme. A woodworker’s shop had a spring-pole lathe. At the top of the hill there was a room with Viking clothing so you could dress out or try on some chainmail. Unfortunately, our tour guide found me at the top of the hill and said it was about time to head for the bus, so I turned around.

Before leaving I checked out the gift shop, which is where Tom and I met up again. As we compared notes, we were ready to go back into the Viking farm, when we realized we were the only people from our bus still in the area. Ooops! It is always bad to be the last ones back on the bus! But definitely not enough time for the two of us to learn everything we needed to know.

On our way back to Aarhus, we talked to Jakob who volunteers at the Living Farm on his days off. He does some spinning (with a drop spindle) and dyeing. He likes trying different plants, roots, and bark to see what color they make. One of his favorite dyes is madder, which is what they used to dye British soldier uniforms like Tom often wears. He has also used woad, an ancient blue dye that uses fermented urine as a mordant.

Our final stop on the tour was in Raastad to see the Raastad Church. Denmark has the highest concentration of surviving church murals anywhere in the world. Most of them date back to 12th and 13th centuries, at a time when the average church-goer was illiterate. The murals tell the stories of the Bible, especially the life of Christ. Over time most of the murals were covered with limewash, which preserved them. Jacob Kornerup (1825–1913) rediscovered the murals and carried out restoration work in 80 churches across the country towards the end of the 19th century.

The Raastad church was built in the 12th century and has some of these restored murals. In fact, the church has not changed much through the centuries, except for the addition of a pulpit after the Reformation. In the heart of this tiny, rural community lies this wonderful treasure with its extravagant and ancient mural.

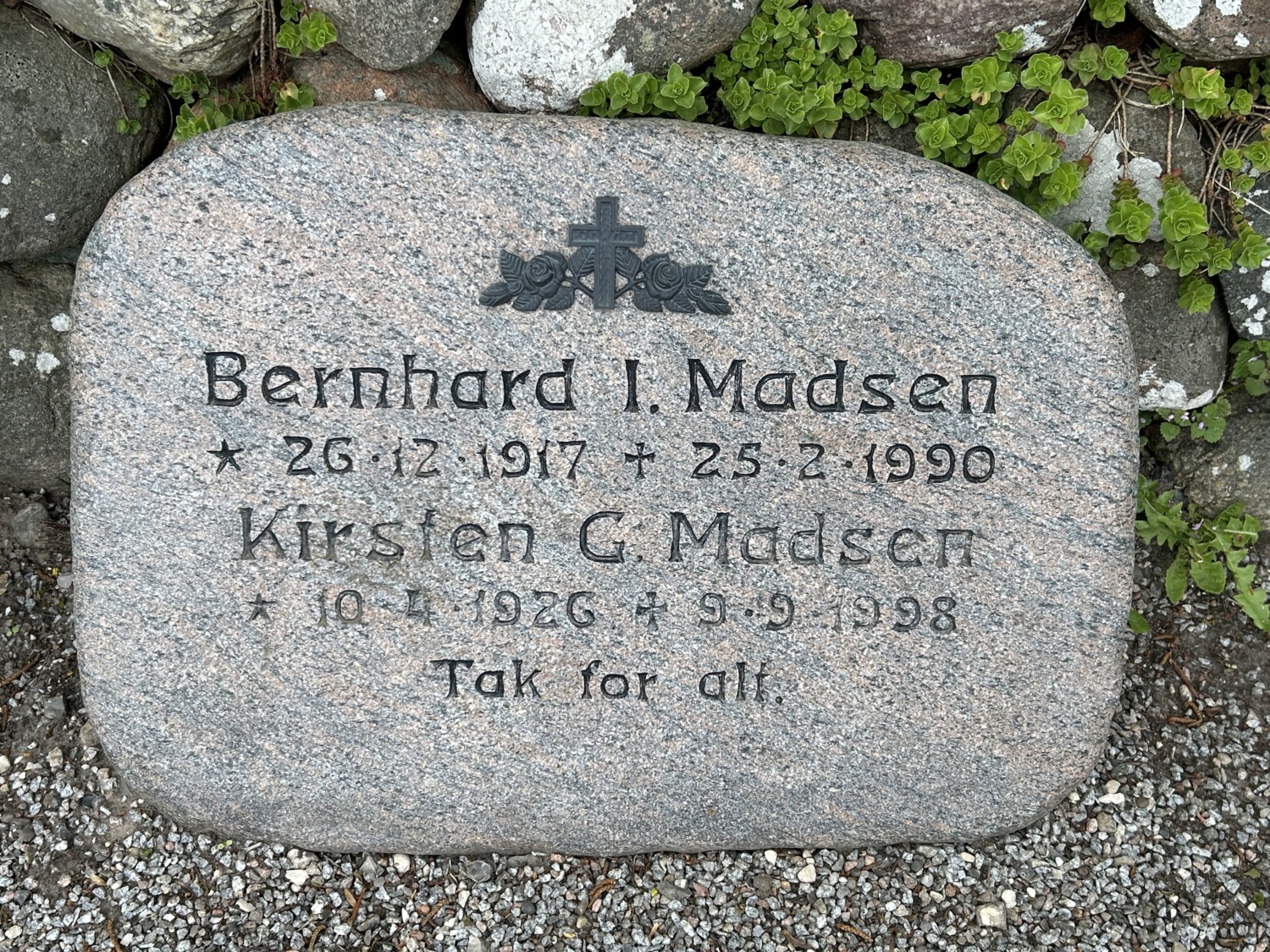

Jakob also explained the small cemetery around the church. Although people have been buried in this cemetery since 1100, the oldest gravestones are from the last 25 years. People in Denmark get the use of a gravesite for just 25 years. Then, having decomposed in an orderly way, another person is buried on top of them. The old headstone can go to the family or gets set aside as a historical marker if the person was important.

This seemed a very pragmatic approach to me, very Danish. After all, most of the visiting to a gravesite is going to be in the first 25 years after a person dies. Tom thought it might make finding your ancestors harder. Many of the headstones had “Tak for alt” on them. I asked Jakob about it, and he confirmed that it meant “Thanks for everything.”

We had a wonderful visit to Fyrkat Viking Fortress and Living Farm. We would have stayed at the farm for a few more hours if we had been able. In fact, Tom suggested we move to Denmark and volunteer at the Fyrkat Living Farm. There would certainly be plenty to learn in terms of living like a Viking.