How much do you know about the Revolutionary War? I think I know my American history pretty well, but I have to admit that I didn’t know much about the Revolutionary War. I’ve been to Boston, Philadelphia, Valley Forge, and Concord but I’ve never really thought about where the war was fought or how it was fought. Aside from George Washington, I couldn’t have named a general from the Revolutionary War on either side.

How much do you know about the Revolutionary War? I think I know my American history pretty well, but I have to admit that I didn’t know much about the Revolutionary War. I’ve been to Boston, Philadelphia, Valley Forge, and Concord but I’ve never really thought about where the war was fought or how it was fought. Aside from George Washington, I couldn’t have named a general from the Revolutionary War on either side.

All that has changed. I’m not an expert, but I have learned a lot about the Revolutionary War in the last month, and, of course, I am going to share it with you. Much of my information comes from “The Complete Idiot’s Guide to the American Revolution” by Alan Axelrod. I like these books and the ” . . . for Dummies” series because they can help you get a good basic grip on any subject. I have also read several books on the Revolutionary War in the Carolinas to get up to speed for our current job.

This week I will start with the causes of the Revolutionary War. Most of us could recite the primary cause: taxation without representation. The American colonists, most of them from Great Britain, were loyal citizens, but Great Britain was an ocean away. Settlers on the frontier wanted protection from the Indians. This became even more important during the French and Indian War, which Great Britain and its colonies won. But, in order to fund the war and the protection the colonists wanted, Great Britain taxed the colonies. When those taxes proved profitable, Great Britain continued to tax the colonies until the colonists felt they were being taxed to death. The British Parliament passed the tax laws but the colonists were not represented in Parliament.

Other issues that caused dissension with the British: in Great Britain only those with wealth owned land. In the American colonies, anyone who was willing to work could own land. Colonists, even those who were the American “aristocracy” were looked down on by the British. In the colonies, any white male could vote or hold office. However, government officers could also be appointed by King George III, so duly elected officials were often arbitrarily replaced with the King’s appointees. These appointees were only out for their own profit, not the good of the colonists.

Taxation without representation, and the British officials who were being appointed to enforce that taxation, united the 13 diverse colonies. Previously each colony had related to Great Britain as an individual unit. Now, the colonies started to see themselves as united against the tyranny of Great Britain. The British enforcement of the taxes, even though most of the taxes were repealed by 1770, caused the colonists to see themselves as a new country, one that didn’t need Great Britain.

Taxation without representation, and the British officials who were being appointed to enforce that taxation, united the 13 diverse colonies. Previously each colony had related to Great Britain as an individual unit. Now, the colonies started to see themselves as united against the tyranny of Great Britain. The British enforcement of the taxes, even though most of the taxes were repealed by 1770, caused the colonists to see themselves as a new country, one that didn’t need Great Britain.

This feeling was by no means universal among the colonists. Many were recent immigrants who had strong ties to the mother country. Rich colonists still sent their sons to Great Britain to be educated. Many of the colonists, however, came from countries besides Great Britain. And when Great Britain flexed its muscles concerning taxes, the colonists wondered what would be next. Religious oppression, from which many of them had fled? Land requirements for voting? Settlers on the frontier were accustomed to carving their own place in the wilderness. They resented anyone telling them how they could live.

Colonial emotions were inflamed by several acts by the British government. First, settlers in the Carolinas had taken to vigilante justice when the British government declined to send troops to deal with outlaws along the frontier. When the “regulators” got out of control themselves, the British sent in armed troops to control them. The settlers resented the British sending troops against the “law-abiding” citizens when they had refused to do so against outlaws.

Second, because of radical anti-British policies being passed by the New York Legislature, the British disbanded the New York Assembly. What little representation the colonists had was being repressed and even loyal British citizens resented this move.

Third, British troops were sent to occupy Boston after a series of incidents. Citizens were required to house the soldiers in their homes whether or not there was room or means to sustain them. Mobs began to form at various times in Boston. One such mob led to the Boston “Massacre” in which five colonists were killed.

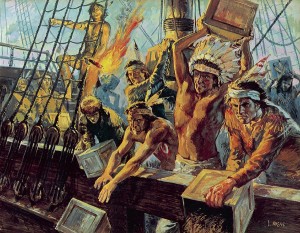

Fourth, protest escalated in Boston with the Tea Party, in which colonists, dressed like Indians, went aboard ships in the harbor and threw British goods overboard. This led to the passing of the “Intolerable Acts” by the British Parliament in retribution. Boston and Massachusetts were severely punished for their defiance. The other colonies knew if Great Britain would do it to Massachusetts, Great Britain would do it to them too.

Fourth, protest escalated in Boston with the Tea Party, in which colonists, dressed like Indians, went aboard ships in the harbor and threw British goods overboard. This led to the passing of the “Intolerable Acts” by the British Parliament in retribution. Boston and Massachusetts were severely punished for their defiance. The other colonies knew if Great Britain would do it to Massachusetts, Great Britain would do it to them too.

Anti-British feeling deepened and twelve of the colonies (Georgia declined) decided to send representatives to the First Continental Congress which met in September of 1774 in Philadelphia. This Congress resolved to withhold taxes from Great Britain until the colonies gained representation, boycott British goods, and declared many of the acts of Parliament unconstitutional. Congress urged each colony to form and train its own militia to resist the British, if Parliament refused to consider the issues passed. The First Continental Congress laid the foundation for colonial unity and organized rebellion.

But how did we get from the First Continental Congress to the Revolutionary War? And when did the war actually start? For the answers to these questions you will have to wait until next week for the next installment of Revolutionary War in a Nutshell.