The third and final day at Chickamauga was, of course, the decisive one for the battle. As darkness fell on the second day, Rosecrans reordered his lines. He did this by shuffling just about every regiment in his army. Instead of allowing them to dig entrenchments where they were and get some rest, he moved regiment after regiment from one spot to another. Finally he was content with the disposition of his troops, most of them close to LaFayette Road, which he still intended to hold.

Most of the Union commanders seemed to feel that one more day of fighting would seal a decisive victory. They did not instruct their men to dig entrenchments, and the exhausted men were glad for the chance to rest. Only General Thomas ordered his men to chop down trees and dig holes to give them some protection in the next day’s fighting.

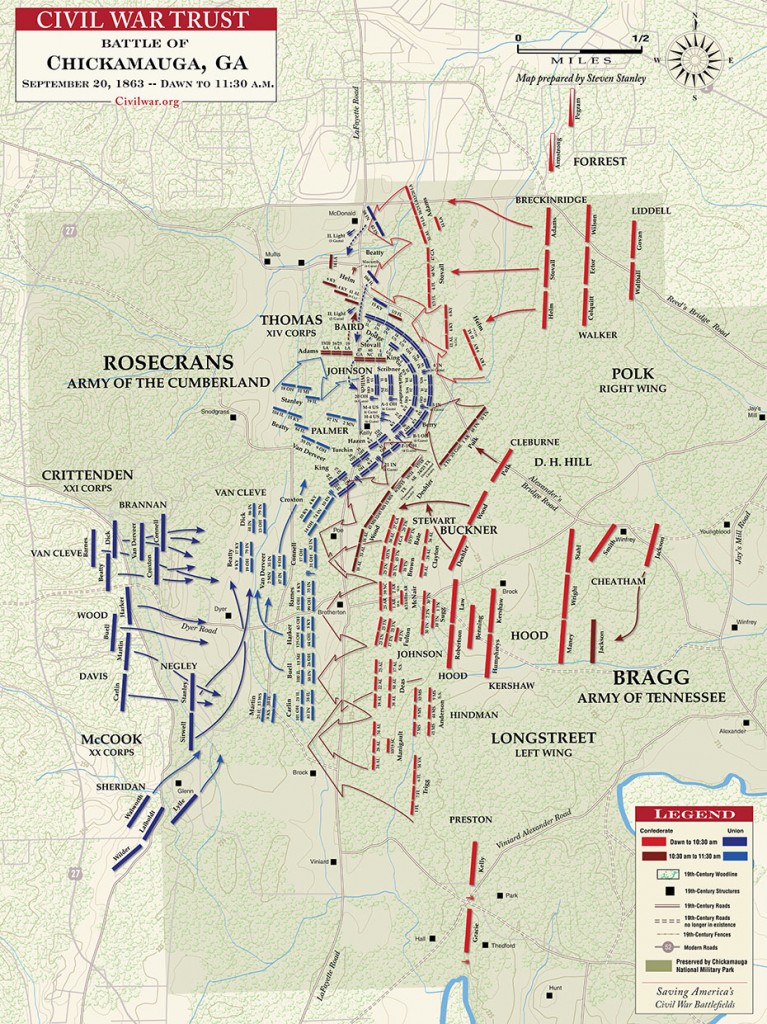

General Bragg issued orders that his Confederate army was to attack at dawn on Sunday, September 20. The attack was to come in a wave, with each unit engaging as the division to its right attacked. General Polk was to begin the attack on the far right of the line. For some reason, Polk decided to have a leisurely breakfast and allow his men to do the same. Then they would draw rations for the day and fill up on ammunition. Finally, at 9:30 – well after dawn – the attack began.

General Bragg issued orders that his Confederate army was to attack at dawn on Sunday, September 20. The attack was to come in a wave, with each unit engaging as the division to its right attacked. General Polk was to begin the attack on the far right of the line. For some reason, Polk decided to have a leisurely breakfast and allow his men to do the same. Then they would draw rations for the day and fill up on ammunition. Finally, at 9:30 – well after dawn – the attack began.

Thomas’s well-entrenched Union troops were able to repulse these first attacks. From this position, the cannon were able to be particularly effective and hold off the attacking Confederate forces. But Thomas was concerned that the Confederates would get around his flank. So he asked General Rosecrans for reinforcements.

General Rosecrans, who had not had any sleep for three days, sent Thomas some reinforcements. The fighting was heavy along the southern portion of LaFayette Road, and Rosecrans decided that sending Thomas the reinforcements had opened a hole in the line. He ordered General Wood to close up the hole. There was no hole in the line, and General Wood knew that if he moved he would create a hole, but Rosecrans had already reprimanded Wood twice for not following orders. Instead of talking to Rosecrans, who was only a short distance away, Wood pulled his troops out of the line where they were fighting and prepared to move them as ordered.

Meanwhile, General Longstreet, far down the Confederate line of battle, had waited impatiently for the right time to put his troops into action. Finally, the battle had moved down the line well enough that he felt he could commit his troops and he ordered them to attack. At the exact place and time that Wood was moving the Union forces out of the line. Does anyone see a problem with this?

Longstreet’s Confederate soldiers now poured right through the gap that had just been created. They were surprised to meet no resistance, so they started looking around for the Union army. The Confederates found them to their right, and they turned and started to fight the Union troops who were already fighting other divisions in front of them. The Union soldiers could not fight in two directions at once so they started to withdraw (retreat) but the sheer number of Confederate soldiers was overwhelming and the retreat soon turned into a rout, with the Union soldiers running away as fast as they could.

Longstreet’s Confederate soldiers now poured right through the gap that had just been created. They were surprised to meet no resistance, so they started looking around for the Union army. The Confederates found them to their right, and they turned and started to fight the Union troops who were already fighting other divisions in front of them. The Union soldiers could not fight in two directions at once so they started to withdraw (retreat) but the sheer number of Confederate soldiers was overwhelming and the retreat soon turned into a rout, with the Union soldiers running away as fast as they could.

As the Confederate soldiers continued up the line, Union troops broke and ran. Commanding officers could not rally the men and many of the officers were terrified and running away as well. The word came to General Rosecrans that the Union army was routed, running away, fleeing to Chattanooga. General Rosecrans decided that he, too, needed to retreat to Chattanooga to bring order to the chaos.

In a short amount of time most of the Union army had cut and run. The far left of the Union army, cut off from the small group of soldiers still holding the north end of the field, tried to find a way around but many soldiers ended up heading for Chattanooga with the rest of the army. By early afternoon, all that was left of the Union army was Thomas’s entrenched divisions on Snodgrass Hill. Some of the retreating Union regiments stopped and created a line on top of Horseshoe Ridge, supporting Thomas’s troops on Snodgrass Hill. Their position was defensible, but could they hold against the entire Confederate army?

Over and over the Confederates charged up the hills, trying to overrun the Union position. Over and over the Union soldiers desperately fought them off. Union regiments ran out of ammunition but the cannon kept firing and finally General Granger’s Reserves, who had been out of the fighting all day, came just in time to reinforce the soldiers in their position. All afternoon the Confederates pushed but Thomas’s forces held strong. Thomas said they stood like oaks, which is why the regiments of the 14th Corp of the Army have an acorn as their symbol. Thomas’s stand on Horseshoe Ridge earned him the nickname, “The Rock of Chickamauga.”

By the end of the day the Union forces were still holding off the Confederate army. Both sides were exhausted and almost out of ammunition. Finally darkness fell, allowing the Union soldiers to leave their position and fall back toward Chattanooga in an orderly withdrawal.

By the end of the day the Union forces were still holding off the Confederate army. Both sides were exhausted and almost out of ammunition. Finally darkness fell, allowing the Union soldiers to leave their position and fall back toward Chattanooga in an orderly withdrawal.

Thomas’s corps saved the Union Army from destruction on the final day at Chickamauga. General Bragg and the Confederate Army claimed a victory, but it was an empty victory because the Union army was now in Chattanooga – the place the Confederate army was supposed to hold at any cost.