Before I tell you more about the battles of the southern campaign of the Revolutionary War, I want to introduce you to three British officers who will be important in these battles. I could talk about lots of people, but that would just be confusing. If I only give you three British officers, you might have some hope of remembering them when I mention them in the weeks to come.

Lieutenant General Charles, Earl Cornwallis, was second in command to Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton, leader of the British campaign in the colonies. When the British decided to expand the war into two theaters (north and south), General Clinton sent General Cornwallis to lead the southern campaign. General Clinton’s instructions were simple: take Charleston and use that as a launching point for a campaign through South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. The taking of Charleston was simple compared to the rest of the instructions.

Lieutenant General Charles, Earl Cornwallis, was second in command to Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton, leader of the British campaign in the colonies. When the British decided to expand the war into two theaters (north and south), General Clinton sent General Cornwallis to lead the southern campaign. General Clinton’s instructions were simple: take Charleston and use that as a launching point for a campaign through South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. The taking of Charleston was simple compared to the rest of the instructions.

General Cornwallis took command of the southern campaign eagerly. As a member of the House of Lords, General Cornwallis had not been in favor of war in the colonies. But, he was a military man, and when his country called, he answered. He had the usual British disdain for the unruly American backwoodsmen whom he thought inhabited the Carolinas. He had no doubt that the superbly trained British army would be able to bring the rebels under control quickly.

Unfortunately (for the British), the Patriots in the Carolinas were not as easily subdued as Cornwallis hoped. The Continental Army in the south had disappeared, but militia, fighting guerrilla style, were still a strong presence. Cornwallis hoped to have an easy time marching through the Carolinas, feted and fed by the Loyalists as they passed through. Like irritating mosquitoes, the Patriot militia would strike fast at small groups of the army, and then disappear into the swamps and forests as quickly as they had appeared. They didn’t win big battles, but they kept the Loyalists from organizing and kept the British army from gaining the supplies they wanted or marching easily through the Carolinas.

In deciding how to deal with the Patriot militia in the Carolinas, and knowing that eventually the Continental Army would renew its presence in the south, Cornwallis decided he would divide his army into three groups. Cornwallis would take the main branch of the army and march through the center of the Carolinas. He would give command of the western flank of the army to Major Patrick Ferguson and command of the eastern flank to Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarelton.

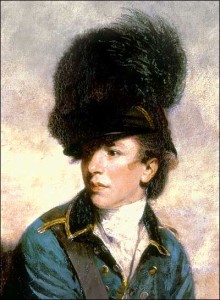

Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton was a young, brash, supremely confident officer who loved to lead troops into battle. During the southern campaign, Tarleton led the British Legion and the 17th Light Dragoons, a cavalry force that could move swiftly to engage rebel militia groups. He was always eager to take the credit for victories and quick to shift the blame for defeats. Tarleton had no qualms about taking whatever he needed for his troops from anyone they passed, so they raided the countryside for horses and food. Tarleton also let his men kill rebels indiscriminately and plunder even the farms of Loyalists.

Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton was a young, brash, supremely confident officer who loved to lead troops into battle. During the southern campaign, Tarleton led the British Legion and the 17th Light Dragoons, a cavalry force that could move swiftly to engage rebel militia groups. He was always eager to take the credit for victories and quick to shift the blame for defeats. Tarleton had no qualms about taking whatever he needed for his troops from anyone they passed, so they raided the countryside for horses and food. Tarleton also let his men kill rebels indiscriminately and plunder even the farms of Loyalists.

Because of their good horses, and Tarleton’s ambition, his troops moved faster than any other in the war. He was known for relentless, lightning-fast pursuits in which he pushed his men and horses to the very limits. He always needed new horses for his troops because he pushed the men until their horses died. Soon after his assignment to the eastern flank, the people in the countryside – Loyalists and Patriots – were terrorized into a form of resentful submission.

Major Patrick Ferguson was an entirely different kind of an officer. Fifteen years Tarleton’s senior, he had been in the military all his life. He resented Tarleton’s favored status and his rapid advancements. Ferguson took command of the western flank gladly, hoping to have a chance for honor and glory.

Ferguson was a charming persuader. He would seek out Loyalists in an area and convince them that fighting with him was their only chance of winning the war. He raised and trained a militia army that traveled with him in the western parts of South Carolina for months. He was effective in holding off the Patriot guerrilla groups and convincing the Loyalists to stay loyal. His base of operations was at Ninety Six, a strongly Loyalist town in South Carolina that had a fort.

Now that you have been introduced to these three British officers, it will be easier to understand the battles in the weeks to come. But before I move on to battles I will introduce you to several Patriot leaders in next week’s edition of The Revolutionary War in a Nutshell.

2 comments