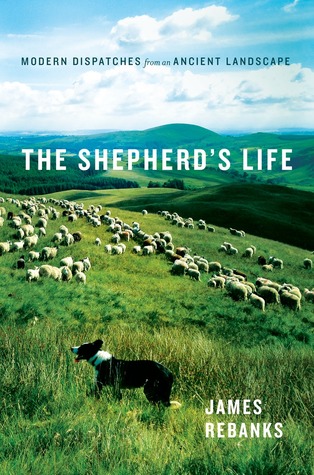

I love books that open my mind to new ideas. “The Shepherd’s Life: A People’s History of the Lake District” is one of those books that introduced me to a new idea and, a month later, I am still thinking about it.

I love books that open my mind to new ideas. “The Shepherd’s Life: A People’s History of the Lake District” is one of those books that introduced me to a new idea and, a month later, I am still thinking about it.

James Rebanks is a shepherd in the Lake District. Being a shepherd is all he has ever wanted to be. His father, his grandfather, and other Rebanks have been shepherds back to the time of the Vikings. But when James went to school, everyone acted like being a shepherd was not “living up to his potential.” All the people he learned about in school were people who conquered other people or made lots of money or were very educated. In other words, none of them were like him or like the people that he enjoyed being around. James rejected this manner of education and dropped out of school as soon as he was old enough.

I come from a long line of farmers, although they were all people who also valued education. I have always felt that we should live up to our potential. For me, this meant getting as much education as possible and working as a professional. And, in my educated snobbery, I thought this is what it meant for everyone. I tend to think of people who drop out of school as people of no account. Reading “The Shepherd’s Life” made me think about things differently.

I value education, but I also think that we need smart people who are tradespeople. I’ve always valued alternative education paths, like vocational education. Hiring the smartest plumber or electrician or HVAC person I can find makes good sense. You don’t have to have a Bachelor’s degree to be a good farmer or shepherd or carpenter. And we certainly want people to do these jobs who see them as a calling and who really want to do the very best they can at them.

“The Shepherd’s Life” opened my mind to another way of thinking about it. Education needs to be relevant to be worthwhile. Unfortunately, we don’t always understand what is relevant or not when we are going through school. I taught Communication classes at Kent State for four years, and I often had students tell me they would never have to make a speech and didn’t see the point of speech class. I would counter that everything we do and say is a kind of communication and we have to know how to do it in a way that gets our point across.

In addition to this idea about education and my prejudices about it, I appreciated “The Shepherd’s Life for its description of a person who wants to do the very best job he can being a shepherd. James Rebanks and his wife are committed to old-fashioned, sustainable farming. They raise their sheep in exactly the same way sheep have been raised in the Lake District for centuries. Their goal is to make enough money to support their family, not to get rich or get a bigger operation.

James talks about his sheep breed, Herdwick, being hefted to the land. The mama sheep teach their lambs which fields are theirs and where they can graze. The lambs grow up and teach the next generation. So the Herdwick breed is territorial and each sheep knows its own pasture. This allows the flocks to graze on the upland hills without extensive fencing separating one flock from another. The sheep knows its place in the world and will head there automatically.

James Rebanks says that he, and others like himself, are hefted to the land. He writes, “This landscape is our home and we rarely stray long from it, or endure anywhere else for long before returning. This may seem like a lack of imagination or adventure, but I don’t care. I love this place; for me it is the beginning and the end of everything, and everywhere else feels like nowhere.”

As I read through “The Shepherd’s Life,” I was struck by the sense of contentment that James Rebanks seems to feel. He works very hard, but takes a great deal of satisfaction in the little things. “The past and the present live alongside each other in our working lives, overlapping and intertwining, until it is sometimes hard to know where one ends and the other starts. Each annual task is also a memory of the many times we have done it before and the people we did it with. As long as the work goes on, the men and women that once did it with us live on as well, part of what we are doing, part of our stories and memories, part of how and why we do those things.”