Whenever I do my demonstration, I am stationed in the Clerk’s Office and get to tell the story of Edwin Denig. Edwin Denig and Rudolph Kurz are my two favorite historical people at Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site. I love talking about them and am constantly trying to learn more about them.

First, the Clerk’s Office. The Clerk’s Office is where clerks did what clerks do. They counted things and kept track of things like inventory, ledgers, and accounts. Clerks made sure enough supplies and trade goods were ordered from one year to the next. They counted the furs and kept track of them until they got on the boat headed for St. Louis. They kept track of inventory as it came off the ships because whiskey, especially, had a way of disappearing on the 1,800 mile journey up the Missouri River.

The Clerk’s Office at Fort Union has two clerk’s desks, lanterns, and several chairs and benches. Even though the building is rough lumber, the clerk’s office has walls lined with muslin and then whitewashed. The whitewash reflected the light and helped the clerks see by lantern or candlelight. It is a bright and (relatively) comfortable room.

Most of what we know about the way the clerk’s office looked is because of sketch done by Rudolph Kurz. Rudolph Kurz was a Swiss artist who spent a year as a clerk at Fort Union in order to sketch life in the west before it was gone. He kept an extensive journal about his year at the trading post. We sell an edited book of his journal in the gift shop, “On the Upper Missouri,” which includes pages of his sketches. His sketches really make the past come alive because the drawings are so realistic. “On the Upper Missouri” is my favorite book about Fort Union. It is a descriptive, readable book about life at a fur trading post.

One of Kurz’s favorite people to write about is the head of Fort Union, Edwin Thompson Denig. Edwin Denig was the Bourgeois, or manager, of Fort Union from 1848 until 1856. He started working in the American Fur Company in 1833 as a bookkeeper. Gradually he rose through the ranks to Chief Clerk and then, finally, Bourgeois. He lived at Fort Union for 21 years and knew it, and the tribes in the area, as well as anyone.

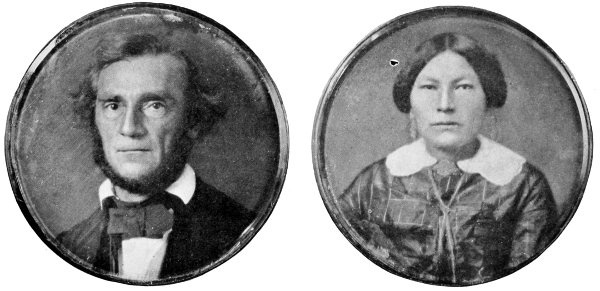

Not only did Edwin Denig manage a very profitable fur-trading post, he was also the first ethnographer of the Native American tribes in the area. He married Hai-kees-kak-wee-yah (Deer Little Woman), a member of the Assiniboine tribe, while at Fort Union. They had two children and she raised his son from a previous marriage as well. Denig also married Hai-kees-kak-wee-yah’s younger sister, in the tradition of the Assiniboine tribe, when the younger sister was widowed. When Denig retired from the fur trade, he traveled with Hai-kees-kak-wee-yah and their children, looking for a place to live. The younger sister chose to stay with the Assiniboine in Dakota territory. Denig married Hai-kees-kak-wee-yah in the Catholic Church in St. Louis and they eventually settled in the Red River Colony, a metis (mixed-blood) community in Canada.

Edwin Denig wrote extensively about the tribes with whom he had come in contact. He wrote five detailed chapters about five of the tribes which was published posthumously in a book titled “Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri.” The book has an excellent biography as an introduction to Denig. Denig intended to write much more about these tribes, as well as three other tribes, but he died suddenly of appendicitis in 1858, when he was only 46. Denig wrote extensively all during the time he worked at Fort Union, aiding in the work of John James Audubon and Father DeSmet, among others.

All of this is a dry recital of the facts of Kurz’s and Denig’s lives, but they were both fascinating men, romanticizing the Native Americans while treating them with paternalistic disregard at the same time. Here is one story about their interactions that might give you a better glimpse into these two men.

Rudolph Kurz started working as a clerk at Fort Berthold, but he soon got a reputation as an Indian killer. He had been sketching portraits of the local Native Americans when a cholera epidemic broke out. Many of the Native Americans died, and they decided it was because Kurz had sketched their pictures. They were prepared to take Kurz out of the fort and kill him. The fur company couldn’t have that, so they decided to send Kurz up the river to Fort Union.

Edwin Denig, as Bourgeois, decided to hire Kurz as a clerk, but used him primarily as an artist. In this way, Denig astutely got an artist for the salary of a clerk. When Kurz’s reputation as an Indian killer caught up with him at Fort Union, Denig suggested Kurz paint a portrait of Denig’s dog, Natoh. Then they could point at the portrait of the dog and at the living dog and point out that the dog had not died. Unfortunately, Natoh was killed by some other dogs shortly after the portrait was finished. Denig had to hide the portrait of Natoh in the attic.

Edwin Denig, however, was not a superstitious man, so he suggested that Kurz paint Denig’s portrait. He had a couple of constraints however. The portrait had to be life-sized and the eyes had to follow a person around the room. Although he protested, Kurz did as Denig instructed. Once the portrait was finished, the men could point at the portrait and tell the Native Americans that Denig was still alive! Fortunately, Denig survived his time at Fort Union.

I have enjoyed my time demonstrating in the Clerk’s Office. I love to tell stories about Edwin Denig and Rudolph Kurz, my favorite historical people at Fort Union.