During World War II, 110,000 American citizens of Japanese descent were incarcerated. Their crime? Looking like the enemy. With little notice, they were forced to abandon their homes and businesses and move to internment camps. Of course, like the Indian reservations, these internment camps were built where no white people wanted to live. Instead of the gentle climate of coastal California, these citizens moved to cold and rugged places far from their homes. While Tom and I were in Idaho, we visited Minidoka National Historic Site, one of these internment camps.

During World War II, 110,000 American citizens of Japanese descent were incarcerated. Their crime? Looking like the enemy. With little notice, they were forced to abandon their homes and businesses and move to internment camps. Of course, like the Indian reservations, these internment camps were built where no white people wanted to live. Instead of the gentle climate of coastal California, these citizens moved to cold and rugged places far from their homes. While Tom and I were in Idaho, we visited Minidoka National Historic Site, one of these internment camps.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order created the camps and ordered all people of Japanese ancestry to report to the camps. The excuse for this horrible action was the fear of sabotage, but the real reason is connected to racism and distrust of people who look different. When Japanese started showing up in California in large numbers in the early 1900’s, white prejudice toward Asians skyrocketed. Leaders passed and enforced laws preventing Japanese immigrants from becoming citizens or owning land.

Minidoka National Historic Site tells some of this story. Unfortunately the site is fairly new in the National Park system. The site was set aside as a National Historic Place in 1979 but didn’t receive any money for restoration until 2008. The Visitors Center is tiny and only open on the weekends. Right now it is paired with Hagerman Fossil Beds so the rangers who staff the site are most familiar with Hagerman. There also aren’t the usual brown signs pointing you to the site. Getting there was kind of hit and miss.

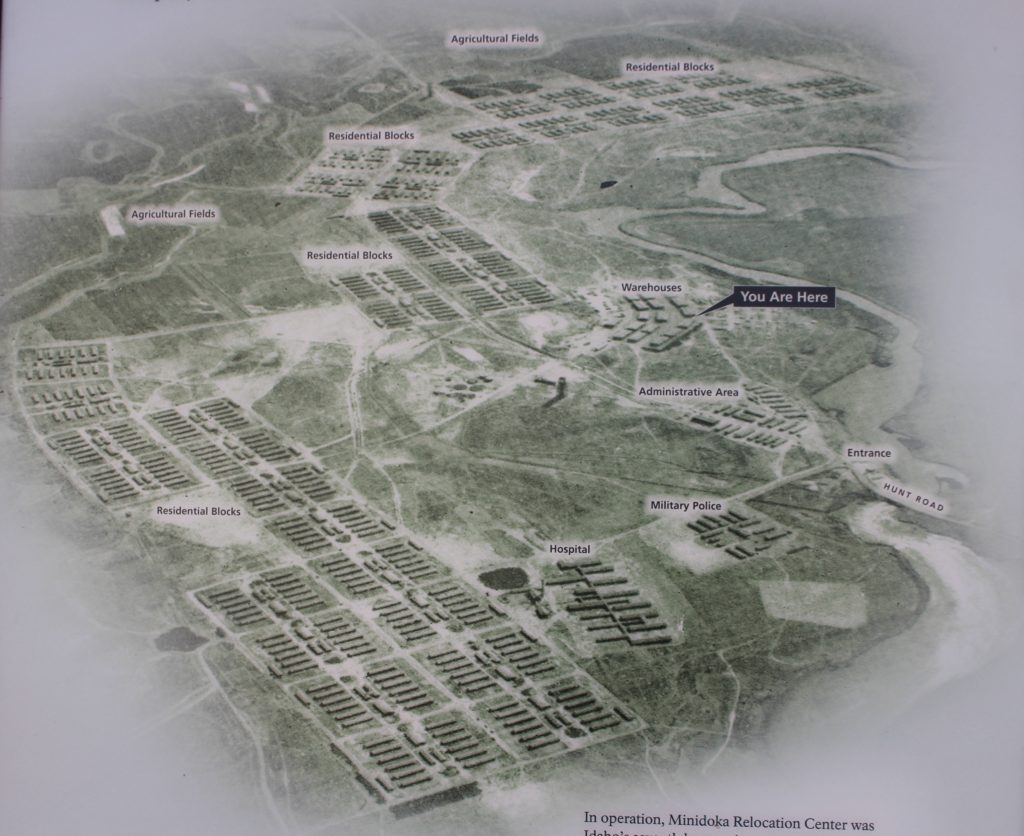

The site itself is open every day during daylight hours. A 1.6 mile trail winds around interpretive signs that talk about the buildings that were in place. There are several old buildings that you can see from the outside.

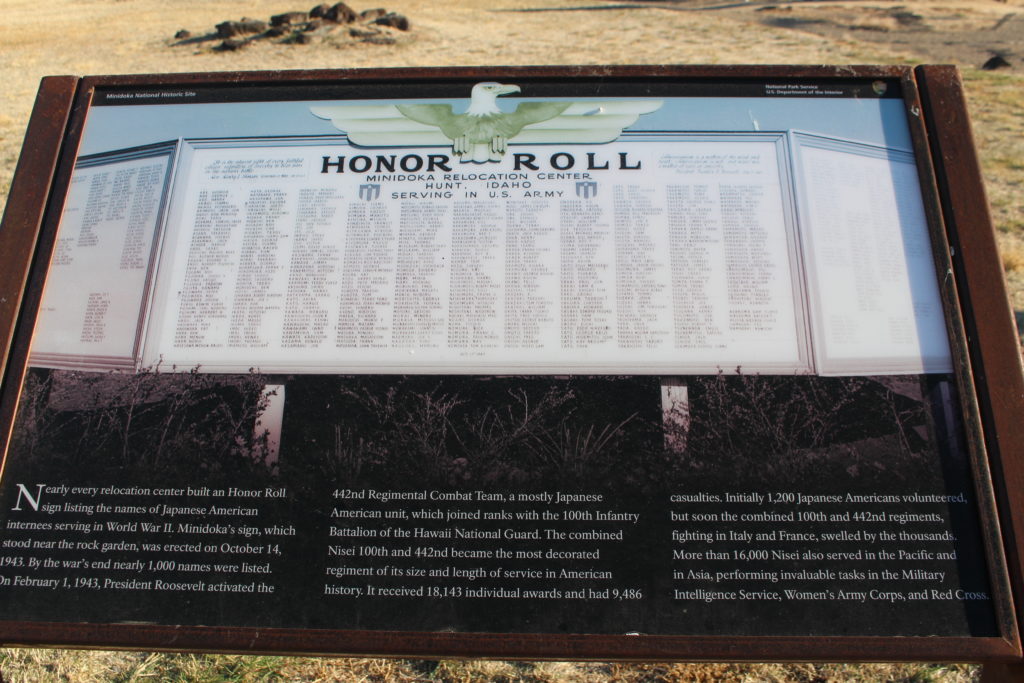

Minidoka was open as an internment camp from 1942 through 1945. During that time the Japanese Americans incarcerated there did their best to make a home and life under difficult conditions. It was hot and dry in the summer with dust everywhere. Winters were frigid and the tar paper shacks where people lived offered little protection against the cold. Despite the difficulties, the Japanese Americans did what they could to further the war effort. Many young men joined the army.

There are ten internment camps scattered across the west, and Minidoka is just one of them. The best one Tom and I have visited is Manzanar in California. It does the best job of interpreting the site and has an excellent museum. We visited it when we were working at Death Valley and you can read about it here. The hope at Minidoka is, over time, they will be able to do a better job of telling the story. Of course, the abandoned buildings and windswept fields tell their own story of citizens illegally incarcerated whose story has been ignored. As the National Park Service develops these sites, the story can once again come to light and gain power.