I have been practicing processing flax during my time here at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. My focus in doing Colonial Living History is textiles and I have a detailed talk from my time at Fort Frederica. But here at Cumberland Gap I have been able to do some hands on experimenting in processing flax.

Flax has been used as a fabric producing fiber for thousands of years. The earliest evidence suggests that flax was used in cloth 36,000 years ago. The history of linen, however, really starts in Egypt. Carbon-dating has proved that linen was used as clothing in Egypt dating back to 8,000 BC. It was prized for its ability to remain cool and fresh in warm weather. Linen is made from the cellulose fibers that grow inside the stalks of the flax plant.

Flax grows on a yearly cycle and does not require a great deal of water or maintenance. This made it perfect for Egyptian farmers. The yearly flooding of the Nile provided enough water and nutrients to germinate the flax seeds, which then required intermittent watering for the next 100 days. Ancient Egyptian linen, although coarse compared with modern linen, was used for clothing, currency, furnishings, decorations and most famously as the burial garment for mummies.

Processing flax occurs much the same way today as it was by the Egyptians. The flax is planted and allowed to grow for about 90 days. Harvesting the flax before seed production produces the best fibers, but some of the flax is allowed to continue to grow to produce seeds. After harvest, the flax is retted. Retting means letting it stand in water until the cells break down so the fiber can be removed.

After drying, the plant is scrutched or beaten on a flax brake in order to remove the bark and pith from the fibers. Then the fibers are brushed on a series of hackles – coarse, medium, and fine – to break the fibers apart and remove any remaining bark. The longer and finer the fibers, the better the linen cloth that can be made from them.

I am really fortunate here at Cumberland Gap because they had a pile of harvested flax sitting in a storage room. The rangers said I could do anything I wanted with it. Joy! I have been experimenting to learn just how to process the flax.

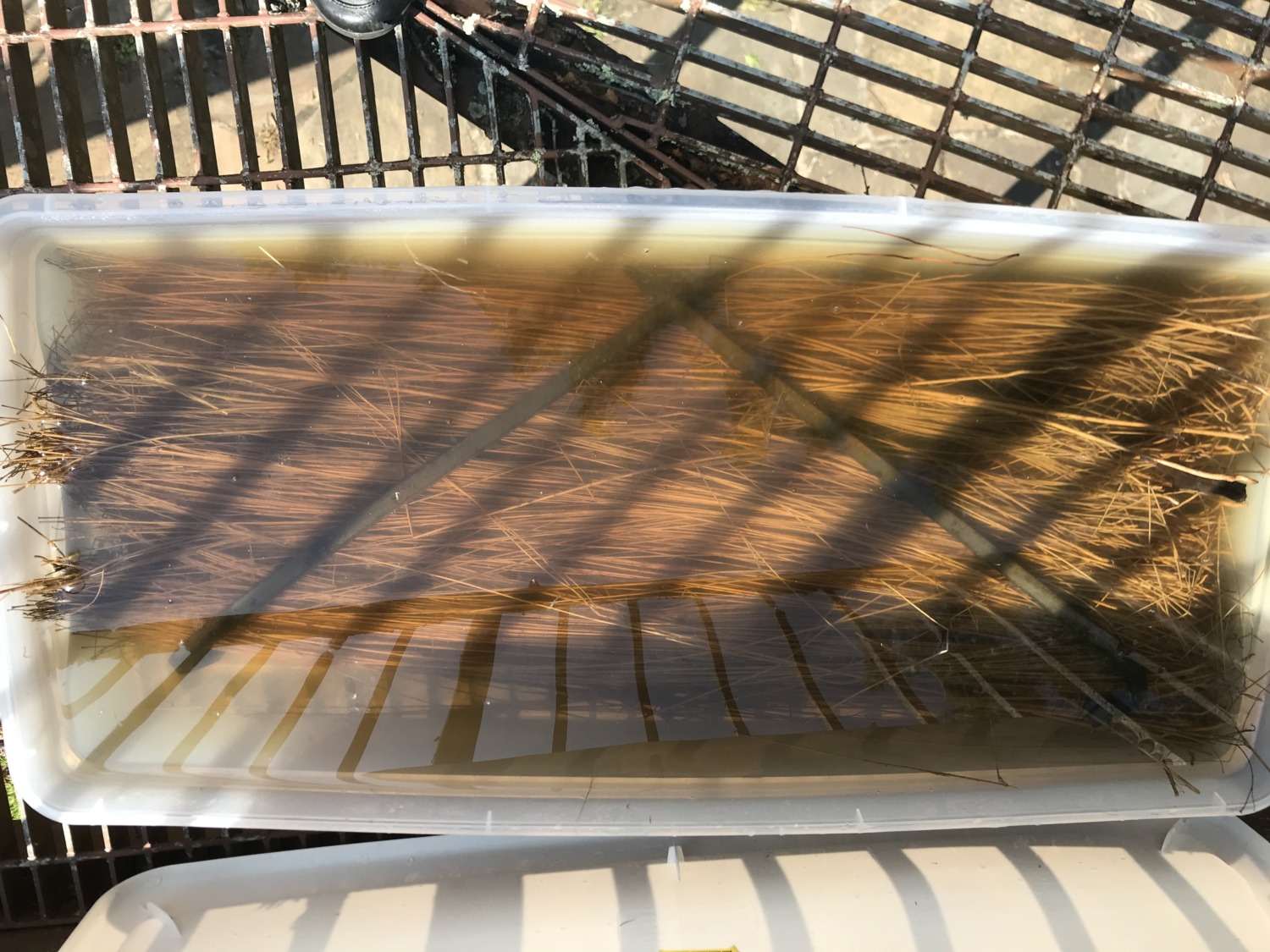

My first step is retting the flax. The rangers here were trying to use the flax brake to get the bark and pith out without retting. It is possible, but very hard to do. But I have never done retting, so there is a learning curve. I got a big, long, flat bin and filled it with water. Then I stuck the flax in and weighted it down with some iron bars. I covered it up and let it sit outside on the fire escape for a week. Then I spread the flax out on the fire escape to let it dry.

Once the flax was dry, I started using the flax brake to break off the bark and pith. The bark and pith comes off a lot easier after retting, although I’m not sure I retted it long enough. I usually only use the flax brake when I have people watching to demonstrate the process. Kids like to take turn using the flax brake and really pounding at the fiber. The bark flies off the fibers all around us.

Once most of the bark is removed by pounding on the flax brake, I take it to the hackle. I only have a coarse hackle, which means I can’t get the fiber as fine as I would like. Maybe when Tom has time, I will have him work on a fine hackle. The hackle is always an impressive demonstration because it is huge, sharp nails. I throw the flax over the tines and pull it down through them. If there are teenagers watching I will let them try it. I can get a decent fiber with just the coarse hackle, but I know it could be better with a fine hackle.

The final step in processing flax is when I spin it. That is when the flax turns to linen. I don’t know why this is the only cloth that isn’t called by the raw material name. Wool is wool. Silk is silk. Cotton is cotton. Flax is linen. But not until it is spun into yarn or thread. Spinning flax takes some practice. It doesn’t need much twist to hold together and the fibers are fairly long, which makes it difficult to know when to add more. I also have to keep it wet so it sticks together better which means I always have a towel on my lap and a bowl of water close by.

I am getting some very nice flax fibers with what I have done so far, but I haven’t experimented much yet. I am going to put a second batch into the retting bin and try leaving it for a few more days, maybe 10. It would also be nice to have a finer hackle to see if that helps produce a nicer fiber.

I knew a lot about flax before, but I am learning even more now. Linen is a wonderful cloth that is cool, durable, and strong. It was as inexpensive and common in the 1700’s as cotton is today. I will keep experimenting during my time here at Cumberland Gap. Maybe I will eventually get enough to weave something from flax I have processed myself. Processing flax is interesting and makes a great demonstration. I expect to be an expert by the end of the summer.