Last week I wrote about three British Officers who were important in the Revolutionary War in the Carolinas. This week I have to give equal opportunity to three Patriot commanders: Nathanael Greene, Francis Marion and Daniel Morgan.

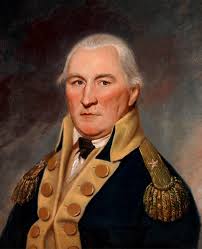

General Nathanael Greene was George Washington’s most gifted and dependable officer, and he served the Commander-in-Chief in many different capacities. Greene was raised a Quaker, but left his pacifist roots in order to fight for the Patriot cause. Greene organized a militia group from Rhode Island, but to his dismay he was not elected as Colonel of the group because he had a limp. He swallowed his pride and continued in the militia as a Private. In 1775 he was promoted from Private to General in charge of all the Rhode Island forces – quite a jump in rank!

General Nathanael Greene was George Washington’s most gifted and dependable officer, and he served the Commander-in-Chief in many different capacities. Greene was raised a Quaker, but left his pacifist roots in order to fight for the Patriot cause. Greene organized a militia group from Rhode Island, but to his dismay he was not elected as Colonel of the group because he had a limp. He swallowed his pride and continued in the militia as a Private. In 1775 he was promoted from Private to General in charge of all the Rhode Island forces – quite a jump in rank!

In 1778 Greene accepted Washington’s urgent request to become Quartermaster General. Although Greene chafed at this desk job, he was a consummate organizer and was able to provision the Continental Army adequately.

The Continental Congress had been unfortunate in the selection of commanders in the South. It had chosen Robert Howe, and he had lost Savannah. It had chosen Benjamin Lincoln, and he had lost Charleston. It had chosen Horatio Gates who lost at Camden and nearly cost the Patriots the war (more on this next week).

When Gates’ successor was to be chosen, Congress decided to entrust the choice to General Washington. On the day after Washington received a copy of the resolution, he wrote to Nathanael Greene at West Point, “It is my wish to appoint You.” The Congress approved the appointment and gave Greene command over all troops from Delaware to Georgia. He was the second-in-command of the entire Continental Army. Greene took command of the southern army at Hillsborough, North Carolina, on December 3, 1780.

General Francis Marion was not a commander of an army like Greene. He was a classic guerrilla leader who would strike at the Loyalists and then disappear back into the swamps of South Carolina. You may have heard of his nickname, “The Swamp Fox.” When the British officers were growing complacent or superior, Marion and his force would strike and then disperse as quickly as they had hit. The British would be sure he had been defeated, only to have strike again miles away.

General Francis Marion was not a commander of an army like Greene. He was a classic guerrilla leader who would strike at the Loyalists and then disappear back into the swamps of South Carolina. You may have heard of his nickname, “The Swamp Fox.” When the British officers were growing complacent or superior, Marion and his force would strike and then disperse as quickly as they had hit. The British would be sure he had been defeated, only to have strike again miles away.

Although Marion was serving in the army when Charleston fell in 1780, he was not in Charleston to be captured with the rest of the army. He had broken an ankle and gone home to recuperate. Because he escaped capture, he was able to recruit and lead a band of guerrillas that would terrorize the Loyalists for the next two years. Marion’s Men, as they were known, served without pay, supplied their own horses, arms, and food. They were fiercely loyal to their leader.

Cornwallis (I wrote about him last week) observed “Colonel Marion had so wrought the minds of the people, partly by the terror of his threats and cruelty of his punishments, and partly by the promise of plunder, that there was scarcely an inhabitant between the Santee and the Pee Dee that was not in arms against us”. Colonel Banastre Tarleton (also last week) gave Marion his nickname after spending months trying to find him. After unsuccessfully pursuing Marion’s troops for over 26 miles through a swamp, Tarleton gave up and swore “[a]s for this damned old fox, the Devil himself could not catch him.”

General Daniel Morgan is considered one of geniuses of the Revolution. He was the first to really figure out how to use militia in fighting an army. Instead of a strike-and-disappear attack, he used militia in concert with the Continental Army. Other commanders tried this and failed, but Morgan used militia as a first strike, who would then retreat and lure the Loyalists into an attack by the main body. We will examine this tactic in more detail in the Battle at Cowpens, but Morgan seemed to be the only commander who figured out how to make it work.

General Daniel Morgan is considered one of geniuses of the Revolution. He was the first to really figure out how to use militia in fighting an army. Instead of a strike-and-disappear attack, he used militia in concert with the Continental Army. Other commanders tried this and failed, but Morgan used militia as a first strike, who would then retreat and lure the Loyalists into an attack by the main body. We will examine this tactic in more detail in the Battle at Cowpens, but Morgan seemed to be the only commander who figured out how to make it work.

Daniel Morgan served as a teamster in the British army during the French and Indian War. The British officers were notorious for looking down on the “backwoods colonials.” Morgan and a British Lieutenant got into an altercation, and the Lieutenant struck Morgan with his sword. Morgan retaliated by punching him. A minor official ordered Morgan to do some menial task, and when Morgan refused, he had him whipped with 499 lashes. Morgan survived, but his back was covered with scars, and he hated the British from that moment on.

After Lexington and Concord, Morgan formed and led a group of Virginia Militiamen to fight in the war against the British. These militiamen had rifles instead of muskets and shot with great accuracy when they had time to reload and cover from which to shoot. Morgan led these men in many battles and was always an able and even brilliant leader. He not only placed his men well, giving them the greatest chance of victory, he was able to inspire them to hold the field. When General Greene took over the southern campaign, he assigned Morgan to hold the western flank.

These are three Patriot commanders who will be important as I begin to describe specific battles in the weeks to come. There are lots of other men who will be introduced at specific battles, but these three men shaped the forces that shaped the outcome of the Revolutionary War.

2 comments