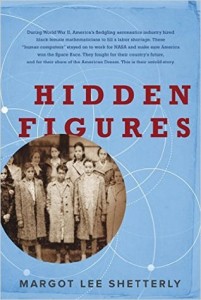

I recently finished reading the book “Hidden Figures” by Margot Lee Shetterly. I became interested in reading the book when I saw a trailer for the movie which will be coming out in January. The movie trailer promised to tell the “untold true story” of the black women who worked at Langley as mathematicians, engineers, and computers and helped launch our country into a new age.

Margot Lee Shetterly grew up in Hampton, Virginia where her father was a scientist at Langley NASA. Margot writes, “as a child, I grew up knowing so many Black people in Science, Math, and Engineering that I thought that was just what Black folks did.” As Margot did the research for “Hidden Figures” she found a group of women who broke the color barrier at Langley and quietly stood against segregation and sexism in the workplace.

Margot starts with the story of the “West Computers,” a group of black women hired during the labor shortage of World War II at the Langley National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). They were computers – people who did the mathematical computations necessary to improve airplanes. These women attended segregated schools, lived in segregated neighborhoods, worked in a segregated room, ate at a segregated table in the lunchroom, and were only allowed to use the one “colored women” restroom.

Despite the restrictions, this courageous group of women gradually worked their way into engineering research groups and rose through the ranks until some reached the classification of engineer and authored research papers. Eventually they helped with the research and equations that sent rockets, and astronauts, into space.

One of the things I found most compelling about the book was the restrictions on the black community into the 1970’s in Virginia. Although I was familiar with the idea of Jim Crow laws, Shetterly does an excellent job of showing how difficult it was for the black community to overcome the systemic discrimination. For some reason, I had the idea that Mississippi and Alabama were the worst states for segregation. Shetterly’s research shows that discrimination was, perhaps, the most intransigent in Virginia. After all, the state constitution of 1902 disenfranchised black men. And the state legislature closed public schools to everyone rather than let them be integrated. Several counties in Virginia went for years without public schools.

Because the book is about multiple characters, it was sometimes hard to follow the convoluted story line. Just when I was really interested in one person, another would be introduced and I would have to go back to the beginning of that person’s history. I understand why Shetterly wrote that way, but it was a little frustrating. There were also times when the book was somewhat dry and repetitious. I also wish the book had included pictures of the people discussed.

I really appreciated the story of “Hidden Figures.” My favorite kind of book is one that invites me to explore a subject further and learn more. It took me a while to read the book because I was constantly looking up segregation laws, federal regulations, and legal responses. I also spent time finding pictures of each of the people mentioned to make them more real.

I am looking forward to seeing the movie “Hidden Figures” in January. It will push us to think about racism and sexism: how far we have come and how far we still have to go.