The Tullahoma Campaign was one of the most brilliant military maneuvers during the Civil War, but very few people outside Tennessee have ever heard of it. Why? Because only 600 men were killed. The Fall of Vicksburg and the Battle of Gettysburg were taking place at the same time and so the Tullahoma Campaign was completely overshadowed.

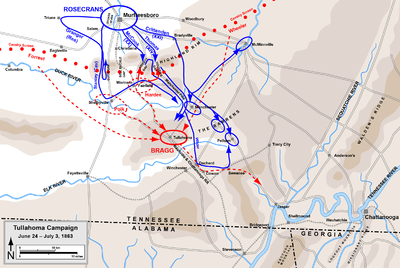

The Union Army, under the command of General William Rosecrans and the Confederate Army, under the command of General Braxton Bragg, had met during the Battle of Stones River (Murfreesboro). This battle was essentially a tie, but Bragg chose to retreat his army into the hills of southeastern Tennessee. He headquartered in Tullahoma and set up a defensive perimeter along the ridges and valleys of the Highland Rim, a front of almost 70 miles. Bragg was particularly concerned with guarding the five roads to Chattanooga through this area. He anticipated that Rosecrans would approach by one of two major roads – through Shelbyville or Wartrace – and left the three mountain passes lightly guarded.

Rosecrans kept his army in and around Murfreesboro for six months (January – June 1963), fortifying it and reprovisioning. President Lincoln begged Rosecrans to resume the offensive against the Confederate Army. Lincoln wrote to Rosecrans, “I would not push you to any rashness, but I am very anxious that you do your utmost, short of rashness, to keep Bragg from getting lost to help Johnston against Grant.” Rosecrans offered the excuse that if he were to start to move against Bragg, then Bragg would likely relocate his entire army to Mississippi and threaten Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign even more. Thus, by not attacking Bragg, he was helping Grant.

Finally, on June 23, Rosecrans was ready to move his army. He had about 60,000 men divided into five corps led by Generals George Thomas, Alexander McCook, Thomas Crittendon, Gordon Granger, and David Stanley. Bragg had about 45,000 men in four corps led by Generals Leonidas Polk, William Hardee, Joseph Wheeler and Nathan Forrest.

Rosecrans started his Reserve Corps, under General Granger, heading the way Bragg expected toward Shelbyville. This, however, was just a feint designed to deceive Bragg. Another unit of the army, Colonel John Wilder’s 17th Indiana Lightning Brigade was dispatched to take the least guarded mountain pass: Hoover’s Gap. (Wilder’s Lightning Brigade is one of my favorite stories and I will write about it in my next Civil War History in a Nutshell post.) This would clear the way for Thomas’s Corps to get through. Another section of the army would head toward Bradyville and try to get behind the Confederate rear. A final division of the army would head to Liberty Gap, the third lightly guarded mountain pass. Success would depend on discipline and timing.

Bragg, as planned, was watching the action in Shelbyville and it took him three days to realize that the Union troops had captured all three mountain passes. Although he planned a counterattack, it took too long to get his troops moving and the Union control of the mountain passes was reinforced. On June 27, Bragg ordered his army to retreat to Tullahoma. As the Union troops continued to push forward, Bragg ordered the Confederate army to retreat to the safety of Chattanooga where they could regroup. They arrived in Chattanooga on July 4.

The Tullahoma Campaign did not receive the positive press Rosecrans felt it deserved due to the fall of Vicksburg and the defeat of Lee at Gettysburg which occurred on the same day. Secretary Of War Stanton telegraphed Rosecrans, “Lee’s Army overthrown; Grant victorious. You and your noble army now have a chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion. Will you neglect the chance?” Rosecrans was infuriated by this attitude and responded, “Just received your cheering telegram announcing the fall of Vicksburg and confirming the defeat of Lee. You do not appear to observe the fact that this noble army has driven the rebels from middle Tennessee. … I beg in behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.”

3 comments